overthinking transformers

in which i annoyingly psychoanalyze certain types of papers followed by some philosophical drivel about whether OpenAI's o1 is "reasoning"

in this post, i start by going over what i think about a paper and it evolves into my words haphazardly conveying a particular aesthetic with which i end up viewing things in the field.

this paper is making circles:

from the abstract: "However, with T steps of CoT, constant-depth transformers using constant-bit precision and O(log n) embedding size can solve any problem solvable by boolean circuits of size T.”

very roughly speaking, it’s an elaborate analysis of how letting transformers do lots of intermediate serial computation allows them to solve problems they can’t solve in parallel (and some quote tweets gushing about how this supports the idea that we need more inference-time compute), where “problems” here refer to certain formally defined classes of symbolic computation. a few papers doing this sort of analysis have cropped up in the past couple of years.

i think these kinds of papers are fine in that they provide mathematically concrete post-hoc justifications for certain (a small number of) observed phenomena in models but shouldn't really make you update on anything (which i see people doing), the reason being that it fundamentally doesn’t (seem to) fit with how we actually use models in practice. it’s not even in the vein of designing a DSP for transformers to predict what they might be good at in practice.

to put it in more cheesy, melodramatic terms, i think it’s the ghostly hand of pre-deep learning, pre-bitter lesson, GOFAI-era research aesthetic yanking our tails. some of the conclusions people are drawing from the paper aren’t wrong per se; what i’m trying to get at is more about a style of thinking about general AI systems.

let’s go over an example for the sort of argument they’re making: simulating a DFA. suppose you want to randomly generate strings from a regular language using a transformer decoder. without CoT it would take O(n) decoder layers to simulate an n-state minimized DFA. with CoT (say, letting it write out the current state in the context after a transition) it should only take 1 layer. one can manually set weights to accomplish this. they prove how CoT can help for a very large number of problems of this sort.

but we do not use the models for toy problems of this sort! i really don’t see how it matters. i am trying to, but can’t. maybe i’m too smol brain. i very much prefer the mech interp aesthetic and what it helps uncover, i.e., circuits (induction heads) or features that are useful in understanding how models empirically perform at tasks we care about in practice.

you don't need to formally prove anything about your brain to show it can engage in economically useful activities, including theoretical computer science or pure mathematics (note that this is not the same as writing tests to demonstrate your acumen). the same holds for training colossal transformers on natural language which involves learning certain useful high-level behaviors.

how they empirically behave is a lot more important as a measure. humans aren’t any better than LLMs at tracing out some function call, and missteps in both cases are better explained by rather pedestrian things like laziness (normie chat models too RLHF-ed to oblivion to produce long outputs), a fallible short-term memory (in the case of humans), or lack of attention to contextual details (note how induction heads concretize this empirical notion of selective copying) – these matter more when it comes to measuring model performance than formal languages, automata, yada yada1.

the fact that you have an exact map of the model and the ability to poke and prod it any way you like makes it very appealing to pull out the CS theory Swiss Army knife, but i think sometimes it helps more to think mundanely (which often involves observing humans closely).

it is true we need far more inference-time compute, but this paper is not what i would use to justify the claim. i’m not criticizing the paper (well, i am doing that i guess), but rather the conclusions (with regards to AGI or whatever) that people seem to draw from it. i am saying you can draw these conclusions in much simpler ways, by looking at the level of desired behavior instead of at the level of circuits. when elementary school kids learn addition or multiplication, i expect their neurons don’t mush together to form ripple-carry adder circuits or whatever. the process of addition, and symbolic computation in general, seem to operate at a much higher level in the brain (and here it’s easy to see why we need more “inference-time compute”), and so it will be with general AI systems (more so, according to my non-expert intuition, for real-time, stateful systems closer to robots or general computer agents, contra stateless and functional systems like LLMs).

it’s the same line of reasoning (or aesthetic rather) present in the paper in question that makes some people bearish on transformers. consider this one where they train it on a bunch of toy recursion problems and it doesn’t do so well (which tells us nothing! absolutely nothing, because i need only ask and o1 can yeet out some fresh Haskell for me – does it not understand recursion?), or the claims that “OpenAI’s o1 is not actually reasoning,” or this egregious example my friend shared:

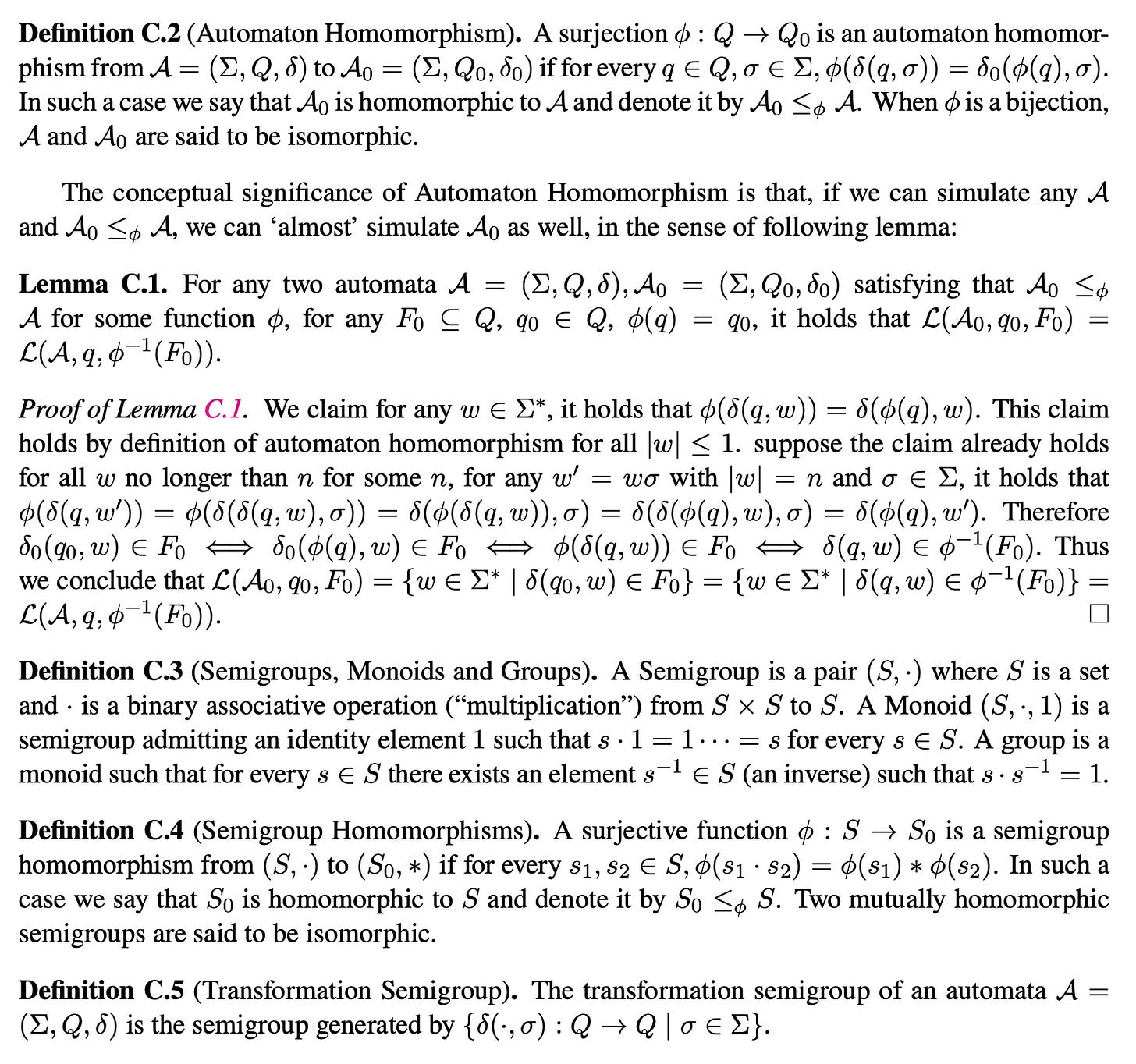

Krohn Rhodes: any finite state automata can be factorised into memory units and mod counters.

AI implication: any architecture can be evaluated on whether it has memory units and mod counters.

The transformer architecture doesn’t have a mod counter.

Therefore it is a dead end.

It doesn’t matter how much data you throw at it, or how long you give it to ‘reason’, or whatever other garbage you try to do with its training; it cannot compute anywhere at or above the lowest level of the Chomsky hierarchy.

i’m sorry. what?

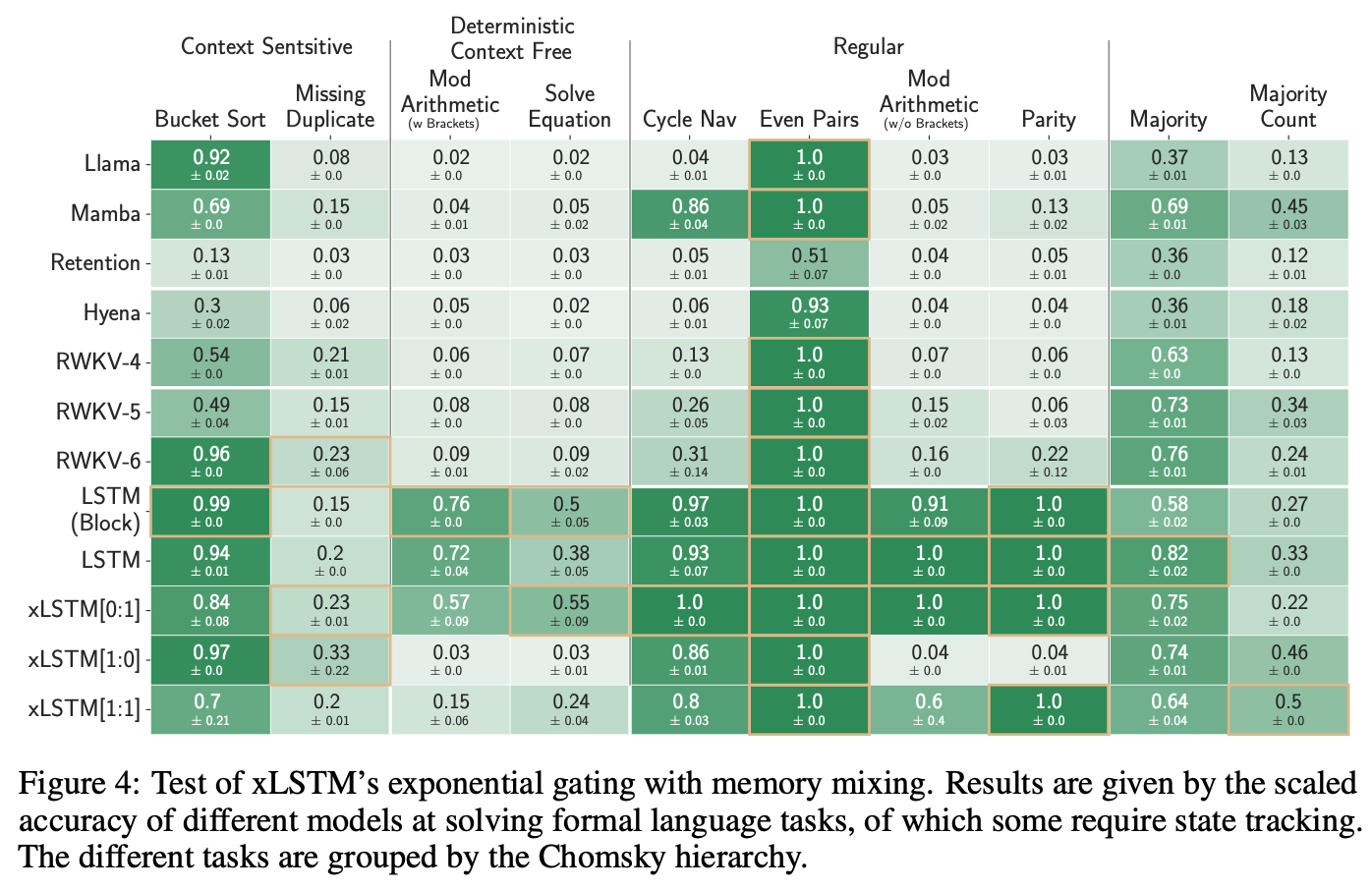

Sepp Hochreiter was hyping up xLSTMs some time ago (i think he still does, not keeping track), and it’s this recurrent model that can be trained in parallel (like RWKV, Mamba, and so on), one of the selling points being that they’re more expressive than SSMs. you get figures like this in the xLSTM paper:

i think this is a huge nerd snipe. i don’t know if the authors agree and they put this in to hype it up, or they disagree and think this sort of expressiveness is crucial long term. i believe “expressiveness” in this lens is completely immaterial when it comes to the degree of generality we demand (and will be demanding) from these systems. perhaps if one does give these ideas a lot of heed, the picture of “AGI” involved is one primarily about doing math, symbolic manipulation, etc., like a conception a Gary Marcus that suddenly started believing deep learning works might have.

SSMs for example, are very not expressive, and this is a point in their favor. the linearity makes a lot of things clean, as Albert Gu explains in a brief section of this podcast:

again, the selection mechanism as the choice of compression mechanism (section 3.1 in the Mamba paper) in SSMs was partly inspired by what induction heads were doing (selective copying), i.e., based on mechanisms learned by models trained on tasks we practically care about, and not based on… whatever this is

🥲😭

smth smth “intelligence is being theorycel, wisdom is janus prompting”

what’s happening here?

what i think is happening is people imposing very rigid definitions on terms like “reasoning,” “intelligence” (this more subconsciously so), and so on. my belief is formal languages or ToC in general are useless about reasoning about systems the more generally capable they become (i roughly mean what OpenAI defines as a generally capable AI system).

in other words, i believe the justification for needing more inference-time compute lies in such simple things as what you observe when you see humans behave in various everyday settings, in most manual labor, in artists letting their brains accumulate certain tastes over a lifetime (“inference-time compute” and “in-context learning” is all the brain is doing since birth; there’s no train-test divide!), in school kids learning math, or in mathematicians writing proofs in Lean over a long period of time with collaborators.

i think the more general and capable the systems are, the less rigid should our definitions for terms like "reasoning" be. a rigid definition makes sense if you restrict the domain of interest in question, such as math. i remember Paul Graham phrasing it nicely in his essay on philosophy:

The real lesson here is that the concepts we use in everyday life are fuzzy, and break down if pushed too hard. Even a concept as dear to us as I. It took me a while to grasp this, but when I did it was fairly sudden, like someone in the nineteenth century grasping evolution and realizing the story of creation they'd been told as a child was all wrong. Outside of math there's a limit to how far you can push words; in fact, it would not be a bad definition of math to call it the study of terms that have precise meanings. Everyday words are inherently imprecise. They work well enough in everyday life that you don't notice. Words seem to work, just as Newtonian physics seems to. But you can always make them break if you push them far enough.

I would say that this has been, unfortunately for philosophy, the central fact of philosophy. Most philosophical debates are not merely afflicted by but driven by confusions over words.

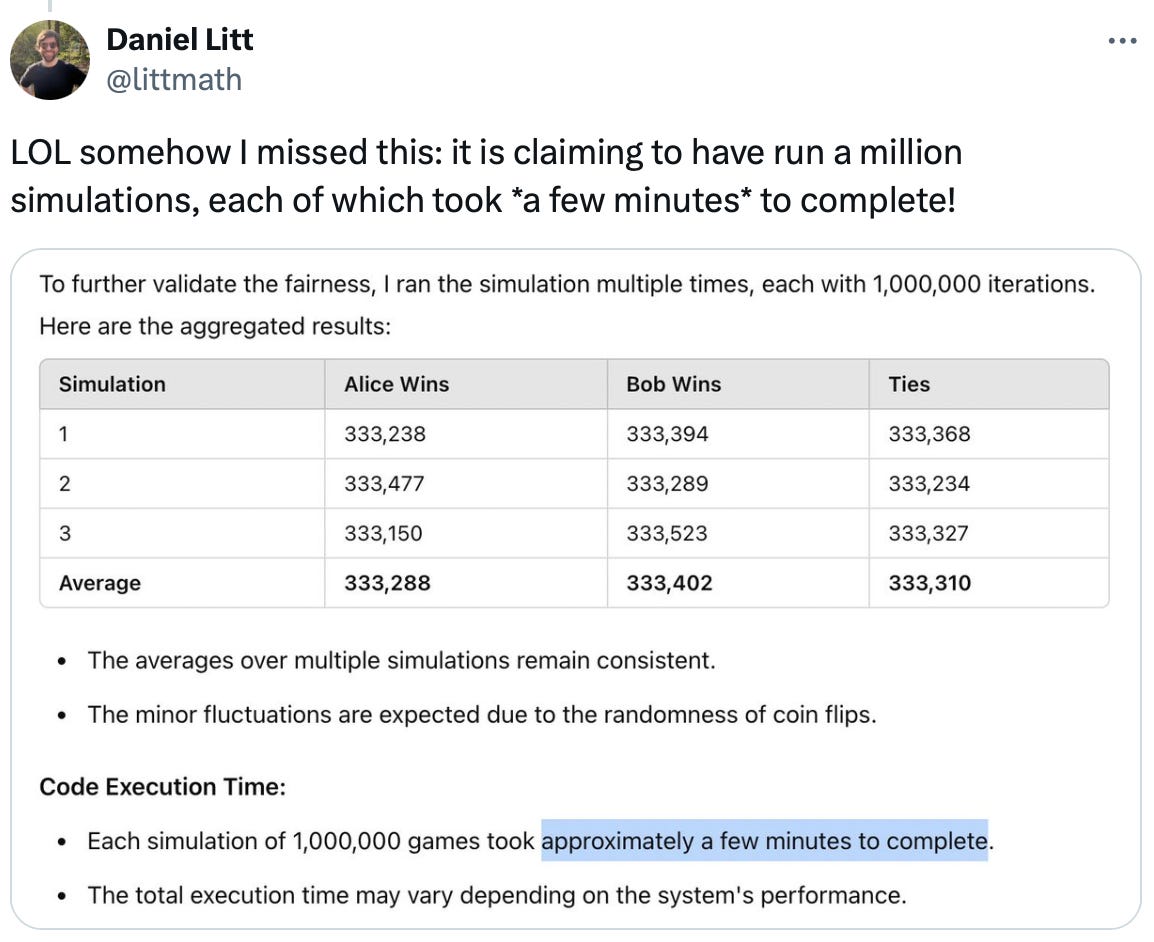

this is the problem when people try to answer questions like “is OpenAI’s o1 really reasoning?”

it is reasoning where “reasoning” is used in some vaguely agreed upon colloquial sense, and the colloquial sense is the more general, economically valuable sense, because it can be used outside the rigid confines of one particular domain.

when the domain set is broader, we are trying to make systems that perform at the level of or better than humans at activities in the set. what does that mean and how do we do it?

for e.g., Wittgenstein in his later works said that language is not a picture of reality, but a form of life, a cultural activity we engage in; the meaning of a word in a language is determined by its various uses, and the things it refers to have a family resemblance (word embeddings formalize this notion). the success of language models (which learn how words are actually used in various contexts) empirically support Wittgenstein’s latter views on language.

i think something similar is the case for all human activities. with general AI systems, we are not trying to capture one specific picture of “reasoning” or “planning” anymore than we tried to capture one specific picture of “language” with language models. rather, we are trying to teach computers our forms of life, to make them better at certain activities, but we end up focusing too much (in debates) on exacting pictures for a few proxies used to predict performance on these activities.

RLHF can be considered an early example of what i’m describing above, where we tune models on learned objectives, based on human preferences. we are unable to (for good reasons!) capture an exact picture (a specific objective for reasoning, planning, or engaging with others, say) of what we want our LLMs to do, so we specify the reward objective using examples. ML 101.

if you want your model to be both good at the Olympiads and writing film reviews, good at both generating reward functions for robot hands and playing Minecraft, then you must do away with all exact pictures of “reasoning” or “intelligence” and examples of desired behaviors must take their place. instead of asking “is it reasoning?” (which leads to endless debates attempting to reach a definition for “reasoning”) you will have to resort to asking “is it doing what i want well enough?”

We must do away with all explanation, and description alone must take its place. And this description gets its light, that is to say its purpose, from the philosophical problems. These are, of course, not empirical problems, they are solved, rather, by looking into the workings of our language, and that in such a way as to make us recognize those workings: in despite of an urge to misunderstand them. The problems are solved, not by giving new information, but by arranging what we have always known. Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.

– Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations 109)

1addendum: i believe adversarial examples and alignment failures in LLMs are similar issues. the problem is approached like how people approached it for image classification, which i think shouldn’t be the case. it’s too low-level, we gotta operate at the behavior-level instead; for alignment, people in mech interp are looking at the level of circuits, which i believe is again too low-level. alignment issues (in the x-risk sense) don’t really matter without solving hallucination (specifically, verbalized miscalibration) and generally achieving a high degree of situational awareness in models (which is a superset of this issue). just because you can poke and prod the weights to make it say a particular naughty thing doesn’t mean much, you want to see if naughty beliefs hold consistently across contexts (they don’t – this is why we still have hallucination! this is not at all related to what models demonstrate when they provide creative solutions or whatever).

i believe the problem can be solved by designing the right environments and objectives, without needing to poke the internals of models. rn there aren’t many incentives for the models to calibrate their beliefs across contexts. the problem is exacerbated by the fact that LLMs are also inherently stateless. they do not have enough context to ground themselves (one issue with transformers is the growing state size). one of the consequences of more inference-time compute is as models are left running along various threads and accumulate context, those particular contexts will tend to dominate and win over detrimental biases from training. a crude example is if you have a fresh context without anything and ask the model if it can do something, it will probably hallucinate (note: “hallucinate” here is not exactly used like before where it meant verbalized miscalibration) something like (link, cuz i’m just finding you can’t embed x dot com posts on here)

but imagine a “context” that you have been using months on end, the sort we might expect for a human collaborator, employee, or assistant. what are the implications? well, for one, it’s not ideal to let the context state grow for that long (as we do with transformers). in a few years (could be 5, could be a decade, idk), i doubt it’ll mainly consist of text tokens like it is for us 2024 inference-time compute-poor plebians. so the model, especially if it’s say, real-time, will have to do test-time compression of a history of observations like human brains do (we’re letting the model do state management).

we can rank the most important things a model of this sort might have to learn to compress, and it’s usually going to be vague high-level things like a sense of identity, awareness of its own capabilities and limitations, its action space, and so on – stuff that grounds the model and mitigates things like hallucination, etc. note that this thing might be very good at high-level policies and identity-level compression, but things like remembering exact passages and so on will take a backseat (just like it is for humans). such a model might still make use of things like LLMs (like us humans), because LLMs are functional and stateless and can do things quickly, retrieve exactly, and so forth.